As a Saudi-led blockade of Qatar continues, the tiny nation needs to evaluate whether its ambitious goals have come at too high of a price.

September 19, 2017By Nicolas Guerrero

Glass-clad skyscrapers rise above a palm-lined waterfront. The financial district, bustling with foreign expats, lies surrounded by the pristine waters of the Persian Gulf. Opposite the harbor is the Museum of Islamic Art, an iconic limestone structure designed by American architect I.M. Pei. The nearby historic quarter is undergoing a multi-billion dollar revitalization as a world-class cultural destination, and the leading fashion houses of Paris and Milan are betting on premium square footage along downtown’s future climate controlled boulevards. A constant flow of jet streams come from the east, where an alluring new airport seeks to become the new hub of intercontinental connections.

Doha—the royal capital of Qatar—spares no detail in showcasing its economic prowess.

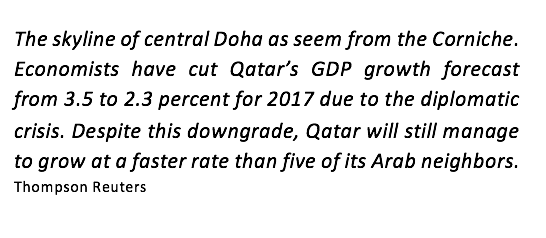

Qatar is a country of inverse proportional dimensions. Of the emirate’s total population of 2.6 million, only 310,000 are citizens. The remaining 2.3 million are mainly western expatriates. It is a small cape, roughly the size of Delaware, jutting north from the Arabian Peninsula. Yet it is the wealthiest country in the world by per capita income. Qatar’s economy is propelled by vast reserves of oil and natural gas (see figure 1). The massive revenues from natural resources are reinvested through the government’s enterprising sovereign wealth fund in prominent assets throughout the world. The Emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, came to the throne determined to follow his father’s legacy of making Qatar push above its weight. The country’s determination to become an influential player in global geopolitics has come at a cost, and now its royal family must decide how to navigate Qatar through the worst diplomatic crisis in its 46 year-long history.

On June 5, 2017 Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Egypt, and Yemen withdrew their ambassadors from Doha, effectively breaking diplomatic relations with Qatar. The countries involved accuse the Qatari monarchs of financing radical terrorist groups, interfering with the domestic affairs of countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and maintaining diplomatic ties with Iran, the Arab world’s most feared adversary.

Qatar, one of the smallest states in the region has managed to be far more influential than its larger neighbors would see as convenient. Mass media is one of the multiple factors that neighboring states fear is key in the potential destabilization of their societies. Al Jazeera is a news broadcaster headquartered in central Doha and owned by the State of Qatar. It has bureaus in six continents and a Western affiliate, Al Jazeera English. The network has provided a platform to extremely controversial figures with implications of antisemitism and Wahhabi radicalism. In 2013 the Egyptian government accused journalists working for Al Jazeera of collaborating with the Muslim Brotherhood and spreading false news. Likewise, Al Jazeera was banned in India after displaying disputed maps of India’s claim over Kashmir on its broadcast. Even though Al Jazeera has denied all allegations of bias and antisemitism, the network is perceived to be the state-owned broadcaster of the Qatari government. The United States Department of State claims that the Qatar government manipulates Al Jazeera coverage to suit the monarchs’ own political interests.1 It appears that through mass communication, Qatar has at least been able to maneuver the direction of popular opinion across the region, in ways that its neighbors find disconcerting.

Figure 1

The Qatari throne has long tried to balance the adversarial forces that surround it as a neutral state intentionally playing dual roles. Doha has provided financial networking to groups that while not linked directly to terrorism, are providing support to individuals who escalate intra-Arab tensions. Yet Qatar also participated in the Saudi–led intervention in Yemen against the Shi’ite Houthi militias, while maintaining robust diplomatic ties to a Shi’ite Iran. Qatar is home to the largest American base in the Middle East, yet in 2013 the Taliban opened an office to “facilitate reconciliation” in Doha a short distance from the United States Embassy. This office was closed shortly after due to international pressure.

The response from Washington has been mixed. The Saudi-led blockade of Qatar came in the weeks following President Donald Trump’s visit to the Middle East. It is still unclear how the talks and closed-door efforts between Mr. Trump and the Saudi monarch influenced their decision to single out Qatar as a threat to the region. The hacking attack on Qatar’s state-run news agency, where allegedly false comments from the Qatari emir regarding Hamas, Israel and support of Iran were published online, seems to have been the tipping point in a heated relationship. President Trump lambasted Qatar shortly after leaving Saudi Arabia in the following Tweet:

“During my recent trip to the Middle East I stated that there can no longer be funding of Radical Ideology. Leaders pointed to Qatar - look!”

Donald J. Trump - 6 June 2017 - 5:06AM

Everything moved very quickly. It had been less than a month when Mr. Trump had met with Hamad Al Thani and discussed Qatar’s purchase of “lots of beautiful [American] military equipment.”

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, former CEO of ExxonMobil implying a grasp of knowledge in the resource-rich region, called for quick cooperation within the GCC. Obama-administration officials have expressed doubt as to whether Mr. Trump realizes that the Al Udeid Air Force base in Qatar is home to two thousand American troops and the launch site for allied military strikes against the Islamic State.

A reliable façade for Qatar’s questionable diplomatic efforts is its role as an economic powerhouse.

Rising 300 meters over the south bank of the River Thames in London is Western Europe’s tallest building. A glittering skyscraper designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano. The Shard—as it is called—is a mixed use glass structure housing corporate offices, including the sleek broadcasting studios of Al Jazeera English on the sixteenth floor. The midsection houses a lavish Shangri La Hotel, with restaurants and suites offering the highest views of any accommodation in the capital. The uppermost tier, is comprised of ten residences, where “residents can wake up to views of the North Sea and have delicacies lifted from the hotel below”. The State of Qatar developed and owns 95 percent of the Shard. It is the crowning symbol of massive Qatari investments in the United Kingdom.

The flow of investments from Qatari funds into quintessentially Western assets has become a staple of the Emir’s efforts to display Qatar’s positive influence. The Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) is as much of a political extension of the government as it is a financial one. In 2012 QIA acquired the London headquarters of Credit Suisse along with a 6% stake in the bank. QIA then purchased the iconic Harrods department store in the London borough of Knightsbridge and opened a branch store in the newly opened Doha International Airport. In France, the wealth fund completed the purchase of football club Paris-Saint Germain F.C. for a total of $130 million. In 2017 the now Qatari-owned football club engaged in the most expensive association transfer in history, paying Brazil’s Neymar a record $198 million to relocate from F.C. Barcelona. In New York, the Qataris have purchased a total of $3.5 billion in properties and paid a record $2.5 billion to BlackRock for a corporate tower in Singapore2.

These investments are dealt through Qatar Holdings, the investment branch of the country’s sovereign wealth fund. It receives periodic funding from the throne. The ruling family has positioned Qatar in the awkward position of avoiding tense confrontation with its neighbors, while maintaining ties to governments openly hostile toward its closest partners. The diplomatic crisis has put a strain on Qatar’s ambitions of grandeur. Qatar Airways, the flagship carrier operates a sprawling fleet of aircraft fitted with the most frivolous of amenities ranging from cocktail lounges to lavatories featuring Armani toiletries. With surrounding airspace closed for Qatar-bound flights, the company has been forced to deviate hundreds of flightpaths southward over the Gulf of Oman increasing the costs of fuel and losing potential passenger loads over longer flight times. In addition, the airline has been banned from operating in any of the countries involved in the dispute.

Not any less problematic is Qatar’s development efforts ahead of the FIFA World Cup it will host in 2022. The blockade on the Saudi-Qatar border is preventing raw materials used in the construction of massive stadiums from entering the country. According to the Financial Times, imports have fallen by 40% compared to last year. The blockade has put a strain on essentials such as food and medical imports. 4000 dairy cows had to be flown in as a basic measure to sustain the population’s needs.

According to the Eurasia Group, Qatar used $38.5 billion to support its economy in the first two months of the diplomatic crisis. This is equivalent to of 23% of its GDP.

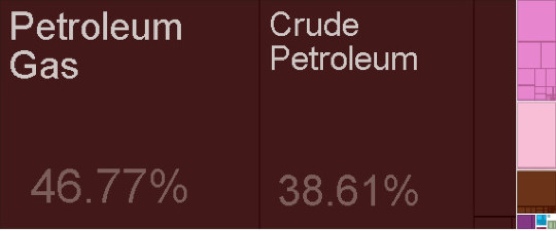

Qatar is not desperate. In a poll conducted of 12 economists at Thompson Reuters, GDP growth forecasts have been cut by 1.2 percent for 2017. Yet Qatar remains the strongest performer in the region. Even with next year’s revised growth forecasts, the country is expected to outperform its neighbors. Qatar’s abundant foreign exchange reserves have cushioned the effects of sanctions, even after hitting their lowest level in five years (Figure 2). In case the reserves become too dwindled, QIA is ready to restock the central bank with $180 billion being held in foreign capital. Continuity in hydrocarbon exports have reassured weary observers of any major shock to the economy.

Figure 2

Side effects to the short-run state of the economy include slightly higher consumer price inflation and higher costs for shipping imports causing delays in ongoing construction projects throughout the country. This may lead to a possible strain in private-sector investment. FIFA and third party organizers of World Cup infrastructure have been made aware of the diplomatic crisis but the event continues as planned. According to Qatar 2022’s deputy secretary of delivery, Nasser Al Khatter, incoming shipping routes have had to diverge to ports in neutral states such as Oman, Kuwait and predictably, Iran.

The region has been in constant turmoil since the end of the Second World War. Some scholars would argue that intra-Arab conflicts and especially Inter-Islamic conflicts date back centuries. Saudi Arabia thinks of itself as something so much more than a country. The House of Saud emphasize their role as custodians of the two holy mosques at Makkah and Medina—the two holiest sites in Islam. They are willing to work with partners and unlikely world leaders to deter any rivalry to geopolitical superiority, especially if it compromises their coalition of Sunni neighbors against the powerful Shi’ite state of Iran, just across the Persian Gulf. Qatar and Saudi Arabia have more in common than they would currently admit to recognize. Both are resource-rich, absolute monarchies with harsh theocratic proclivities. Yet their quest to tweak the definition of sovereignty and be unique players on the regional stage led them to play a game of chicken and show the West which state would turn on the other’s implied weaknesses first. For now, Saudi Arabia has the upper hand and their demands will echo those of smaller Arab states, but geopolitical ambitions also imply that two rational actors eventually see the world through the lens of realism.

_________ References

1Booth, Robert. (2010, December 5) Wikileaks Cables Claim Al-Jazeera Changed Coverage to Suit Qatari foreign Policy. Retrieved From https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/dec/05/wikileaks-cables-al-jazeera-qatari-foreign-policy

2Qatar Investment Authority. (2017, September 18) Retrieved from http://www.qia.qa/Investments/Investments.aspx

3United States Department of State Bureau on Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. (2011, April 8) 2010 Qatar Report on Human Rights Practices. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2010/nea/154471.htm